|

No one on my volunteer list showed up, but luckily Alejandro Zuniga and Connor McGaughran came to my aid for the August 18 clay dig. More accurately, it was clay prospecting. The idea was to get samples that my advanced students will be testing this fall. More than 5 years ago Walter Heath and his students processed quite a lot of clay that was dug on high ground, on the Eastern edge of the East 40. We have been working with that wonderful stash of clay ever since. But that clay isn’t going to last forever, and before we do any large or even medium scale processing of clay, I want to know what we’re going to get. For comparison, I went to one of the lowest lying areas. We took three 5 gallon buckets of clay, the first 18 inches down, the next about 30 inches down and the last bucket at 44 inches in depth. The color became more purely orange/gold the deeper we went. In addition to testing the clay locations, I want to compare dry vs. wet processing. So I’m not only going to test the new location with the existing clay which was wet processed, but the new location with clay from the old location that will be dry processed. Luckily for me, there is a significant amount of quite pure clay that has been sitting in a pile in be old location! There are advantages and disadvantages to either dry or wet processing of clay. I fear that the wet processing that was originally done may be superior, but before I go there I want to test for myself. Is a significant difference, which is easier, and which is gives the better quality of clay? Both wet and dry processing use screens of decreasing size first to screen out larger things likerocks and roots etc., then to get increasingly fine particles of clay with screens that have smaller and smaller openings for the material to pass through. In the wet processing, gravity is used as well; the heavier materials fall to the bottom of the barrel while the lighter ingredients are pumped of the top into the next bucket and the process repeated until you get the level of fineness that you want.

The original wild clay from the East 40 we have been using, until mixed with other ingredients into a clay body, is very brittle. It lacks plasticity, that is the soft pliability that we want in clay. It cracks very easily, and it’s hard to cut it without tearing the clay. On the plus side, it has low shrinkage and beautiful color. It’s obviously iron-rich, but I don’t know the precise chemical composition. Maybe I can find someone in the chemistry department willing to test it. I think it’s unusually high in alumina, because on pots made with the clay even glazes known to be very runny stop being runny. It is actually a spectacular glaze ingredient, a kind of mysterious “special sauce.” I was really happy we were able to get samples from a new location at 3 depths to test. Even just processing and testing small amounts is a lot of work. Keep checking in to this blog to see how that evolves!

0 Comments

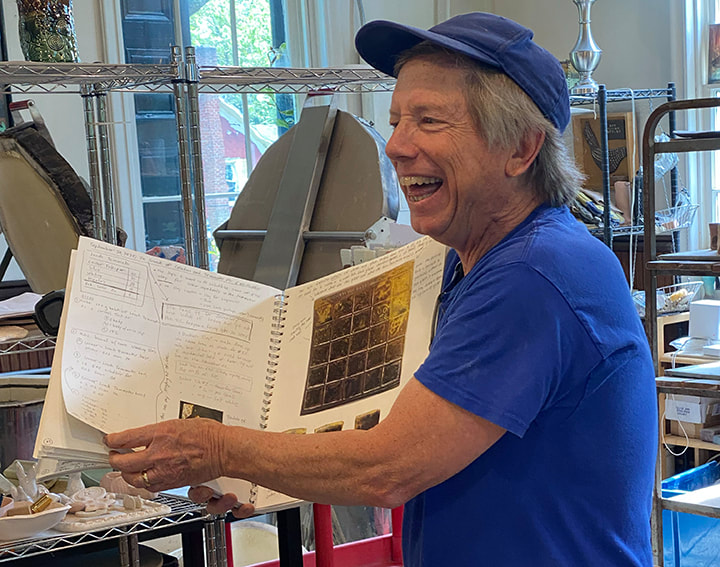

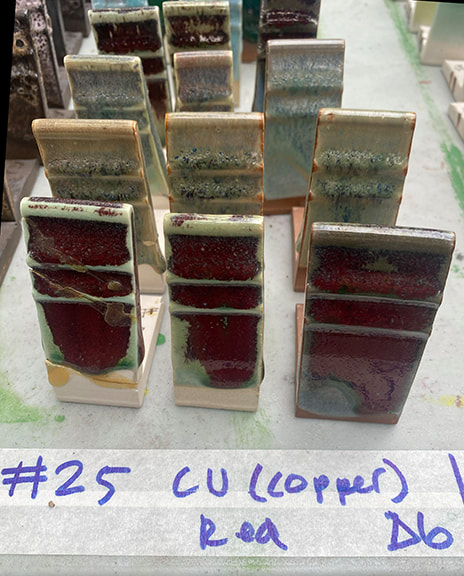

John Britt with SOME of the tiles he brought with him, showing the logic of what we were doing in the workshop. He had 40+ base glazes, and a sheet with 11 colorants that would get added to each glaze. Each person in the workshop made a different base glaze, made 11 different versions and applied each of those to tiles made from 3 different kinds of clay. There are thousands and thousands of glaze recipes online and in print. But John Britt’s books have such a well organized variety, I just don’t bother looking elsewhere. His YouTube free glaze class is amazing, when I came back to ceramics after many years, it not only removed the rust from what I could remember but gave me a more thorough understanding than I had before. I really didn’t want to do another workshop so soon after the Josh DeWeese one at Peters Valley, but it was John Britt close to home, how could I pass it up? After making my own paint, I already had ground up rock when I started teaching ceramics, so it was a pretty natural segue for me to start formulating glazes. It’s true I also listened to lots of Phil Berneberg’s videos and read a bunch of good books, but John Britt is definitely my glaze hero. As much as I’ve learned on my own, I had never taken a class specifically in glazes. John was so systematic and organized in the way he structured the class that it helped me organize my own thinking about glaze development, and how I might present things to my more advanced students. The workshop was hosted by Kettle Creek Pottery, a really lovely pottery studio owned by Amy Manson. It was a great group of people. My moment if glory is when John asked me if he could show my notebook to the class! I got a photo of him holding up my notebook which I of course pasted into that notebook.

|

Cindy VojnovicArtist & Educator Archives

September 2025

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed